Note from Randy Alcorn: This is an expanded version of a book review I did for The Gospel Coalition a few weeks ago. For word count purposes, I needed to edit out some important things I wanted to say in that article, but I have included them in this one (hence it is 40% longer). This is more than a book review—it is a reflection on a battle of worldviews that many churches and individual Christians are sadly losing. It’s also a call to take greater efforts to teach our young people to understand and defend their faith in Christ in a culture that is increasingly hostile to the teachings of Scripture.

Bart Ehrman is professor of religious studies at University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. He also teaches eight of The Great Courses’s widely acclaimed Bible and Christianity classes, and has a part in 78 others. (This is odd, since featuring Ehrman as their primary professor on biblical issues is comparable to selecting N.T. Wright or Wayne Grudem to be their go-to authority on atheism.)

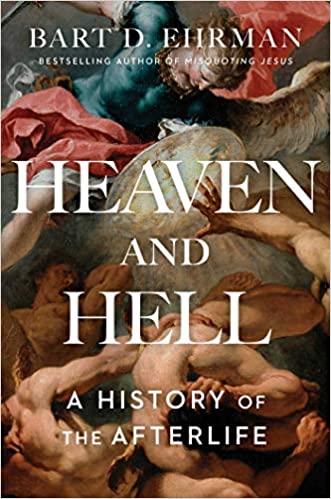

The subtitles of Ehrman’s books, including his five New York Times bestsellers, capture his premises: e.g., Misquoting Jesus: The Story Behind Who Changed the Bible and Why, How Jesus Became God: the Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee, and Forged: Writing in the Name of God—Why the Bible’s Authors Are Not Who We Think They Are.

Why even talk about books like this? Because they are having a widespread and powerful influence. Paul warns us of the human proneness to fall prey to false teachers who deny biblical truth: “For the time will come when people will not put up with sound doctrine. Instead, to suit their own desires, they will gather around them a great number of teachers to say what their itching ears want to hear. They will turn their ears away from the truth and turn aside to myths” (2 Timothy 4:3-4).

False teachers influence the church from both inside and outside, but outsiders gain special credibility when they are former insiders. In this era of escalating deconversions, #exvangelicals, and the “Dones” (with church), Ehrman is a major instrument in countless readers’ downward spiritual trajectory. (Skim through some of the 4,000 reviews of his books on Amazon, and you’ll see how weighty his influence is.) His books and teachings online and through the Great Courses are, from one viewpoint, liberating people from a narrow, oppressive, and outdated Christian faith that their parents and pastors imposed on them. (From a different viewpoint, this liberation is bondage in disguise.)

Same Message, New Focus

Whenever I read an Ehrman book, déjà vu kicks in. His core message is always: “Christians are dead wrong; I know because I used to be one before I became enlightened.” Each of Ehrman’s books deals with something else Christians are wrong about; and his newest, Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife, is another volume in his expanding canon of deconversion doctrine.

Whenever I read an Ehrman book, déjà vu kicks in. His core message is always: “Christians are dead wrong; I know because I used to be one before I became enlightened.” Each of Ehrman’s books deals with something else Christians are wrong about; and his newest, Heaven and Hell: A History of the Afterlife, is another volume in his expanding canon of deconversion doctrine.

Ehrman speaks with the authoritative tone of a historian-philosopher, a wise sage, unfolding humanity’s preoccupation with death and the fear of death. Beginning with the Epic of Gilgamesh, he then examines Homer, Virgil, Plato, and other ancients. Along the way he interjects his belief that there’s no need to fear death, since it’s simply ceasing to exist (the very thing many people fear).

Arriving at the Bible, just one more myth to Ehrman, he presents what he calls the “older Hebrew view” that death is the final end, followed by nonexistence. He then addresses the “later Hebrew position” on resurrection and Judgment Day from the intertestamental era.

While he says little to refute pre-Christian views, once Ehrman gets to the historic Christian view of the afterlife, he conducts an all-out verbal siege. But he doesn’t rant and rave; he calmly presents his assertions, such as that Jesus and Paul disagreed on much, including the way of salvation, but shared a disbelief in an eternal hell. He says both of them, and the author of Revelation (whom he’s certain wasn’t the apostle John), taught annihilationism. He simply ignores or reinterprets passages to the contrary (e.g. Isaiah 66:24; Daniel 12:2; Matthew 25:41, 46; Mark 9:43,48; 2 Thessalonians 1:9; Jude 7, 13; Revelation 14:9–11; 20:10, 14–15).

Ehrman’s thorough and excellent treatment of Homer, Virgil, and Plato stands in stark contrast to his awareness of how Christians historically handled the teachings of Jesus, Paul, and Peter. Ehrman studies the writings of critics with whom he agrees, but I have the impression he relies more on his memories of what he heard at youth group, Moody, and Wheaton than on actual research of what evangelical scholars say. (This may be because “evangelical scholars” is to him an oxymoron.)

Interestingly, though Ehrman doesn’t believe there is a Heaven, he leaves room for its possibility:

I certainly don’t think the notion of a happy afterlife is as irrational as the fires of hell; at least it does not contradict the notion of a benevolent creative force behind the universe. So I’m completely open to the idea and deep down even hopeful about it. But I have to say that at the end of the day I really don’t believe it either. My sense is that this life is all there is. (294)

However, Ehrman is certain he isn’t wrong about Hell:

Are we really to think that God is some kind of transcendent sadist intent on torturing people (or at least willing to allow them to be tortured) for all eternity, a divine being infinitely more vengeful than anyone who has ever existed? …Even if I instinctually fear it, I don’t believe it. (293–94)

At the end of the book Ehrman quotes from ex-evangelical Rob Bell:

In [universalism], the love of God knows no bounds and cannot be overcome. . . . In the words of one modern Christian author, once himself a committed evangelical with a passion for the biblical witness, in the end “Love Wins.” (290)

Ehrman seems to offer universalism as a backup position to his naturalistic worldview. He’s saying, in essence, “I don’t believe in an afterlife, but if there is one then everyone will be in Heaven.”

He goes on to essentially applaud the rise of universalism in Christian churches: “Harkening back to Origen, and Paul before him, these committed believers maintain that in the end no one will be able to resist the love of God. . . . [E]veryone will be saved” (290).

Opinion Isn’t Proof

I admire Ehrman’s skill as a persuasive communicator. He knows how to lay out his position with great effectiveness. (Never mind that this entails considerable overstatement and omission of dismissiveness of evidence to the contrary.) Sadly, he denies the One who gave him those gifts, which makes me wish for the sake of others that he were less eloquent than he is.

Ehrman carefully uses selective information which—in the absence of evidence to the contrary—makes it seem obvious to the jury, his loyal readers, that he is always right. Ehrman would make a skillful defense attorney or prosecutor, as he could argue either side and in the absence of opposition would win his case ever time. (Hence the vulnerability of uninformed believers or unbelievers who read his books.)

Ehrman frequently states what he believes as if opinion constitutes proof. For instance, he emphatically says, “There was a time in human history when no one on the planet believed that there would be a judgment day at the end of time” (8). Really? No one? Does he have private access to an ancient poll taken of every living person?

Ehrman writes in a footnote:

Some readers may wonder why I am not contrasting this view of Job with the famous passage of Job 19:25–26: “For I know that my Redeemer lives, and at the last he will stand upon the earth. And after my skin has been thus destroyed, yet in my flesh I shall see God” (ESV). (301)

I was one of those wondering readers! Ehrman negates Job by citing a Jewish scholar who says, “The text has been garbled and we cannot tell exactly what Job intended to say.” This scholar adds, “Job is almost certainly not talking about seeing God in the afterlife.”

I consulted 12 major translations by different teams of Hebrew scholars, some of whom certainly don’t hold to biblical inerrancy. Their translations contain only minor differences in word choice. All of them suggest Job is indeed speaking of seeing God in the afterlife and affirming that, in what seems clearly to refer to the resurrection, he too will stand with that Redeemer upon a redeemed (New) Earth.

This is just one example of Ehrman’s practice of (1) inaccurately conveying what the Bible says; (2) accurately conveying what the Bible says, then declaring it’s wrong; (3) arguing the text really doesn’t say what Christians believe it says (why would that matter if what it really says is also wrong?); and (4) citing Scripture in support of his contentions, even though he regularly dismisses Scripture’s validity.

When researching my book Heaven, I read more than 150 books on the subject, including many I disagreed with. Yet, in reading Ehrman’s book, I saw no evidence that he had read a single evangelical book on Heaven, though he did manage to cite one on Hell (containing arguments for annihilationism and universalism).

While his footnotes reflect extensive research in ancient Greek texts, he seems largely unaware of what the Bible or evangelical Christians actually claim about Heaven—the New Earth. He refers to Revelation 21:1, and recognizes the teaching of bodily resurrection, yet doesn’t develop what the Bible teaches about the eternal dwelling place of God’s people. I don’t expect him to agree with that teaching, but in a book called Heaven and Hell, I would expect him to give it a chapter, or at least a paragraph or two.

With a few exceptions when he admits he’s not certain, I’m struck by Ehrman’s normally unswerving confidence that he is 100 percent right. He is, just like evangelicals, relying on an ultimate authority—but instead of the Bible, it’s his own intellect. Delivered from that “intellectually feeble” life as an evangelical, his opinions about the Bible, Jesus, and the Christian faith are his creed, the objects of his faith.

Anyone who grounds his life on the belief that Jesus is not God, not the King of Kings or Judge, is naturally going to be resistant to any evidence that He is. After all, a great deal is at stake. The vested interests in not believing in God are every bit as strong as those in believing in God. “Every spirit that acknowledges that Jesus Christ has come in the flesh is from God, but every spirit that does not acknowledge Jesus is not from God. …They are from the world and therefore speak from the viewpoint of the world, and the world listens to them” (1 John 4:2-3, 5).

Apostle of Deconversion

As he does in most of his books, Ehrman seeks to build credibility by sharing his testimony of conversion to unbelief, thereby marketing himself as a reverse C. S. Lewis. Lewis was an academic intellectual who moved from atheism to agnosticism to deism to biblically based Christianity, and in the process burnt academic bridges.

Ehrman, however, professed faith at age 15 at Youth for Christ, then attended Moody Bible Institute and Wheaton College. He was a card-carrying evangelical. His exodus from evangelicalism began when he went to Princeton Seminary, where he lost his faith in the Bible and Jesus:

[At Princeton] my scholarship led me to realize that the Bible was a very human book, with human mistakes and biases and culturally conditioned views in it. And realizing that made me begin to wonder if the beliefs in God and Christ I had held and urged on others were themselves partially biased, culturally conditioned, or even mistaken.

These doubts disturbed me not only because I wanted very much to know the Truth but also because I was afraid of the possible eternal consequences of getting it wrong. . . . What if I ended up no longer believing and then realized too late that my unfaithful change of heart had all been a huge blunder? Wouldn’t my eternal soul be in very serious trouble? (xvi)

Ehrman appears to believe his studies at Princeton were guided by objective truth and his rejection of the Christian worldview was a courageous submission to this truth. Ehrman’s lack of self-awareness is evident when he claims, “In this book I will not be urging you either to believe or disbelieve in the existence of heaven and hell.” No reader could imagine Ehrman is urging belief in Heaven or Hell. But it seems intellectually dishonest to say he isn’t encouraging disbelief in them. Arguably that is a central purpose of the book.

The names of C. S. Lewis, Francis Shaeffer, and Lee Strobel often show up in the testimonies of those who had intellectually resisted belief in Jesus but came to faith. It’s now common for Ehrman to be credited in someone’s deconversion, particularly because of his credentials as a convinced insider who left the fold to become a vocal skeptic.

In fact, to understand Heaven and Hell and Ehrman’s other writings, we must grasp that his deconversion redirected, rather than removed, his evangelistic zeal. It’s not that he’s no longer on a mission, but that his mission has radically changed. Many people have quietly lost their faith, but Ehrman didn’t go gently into the night. Instead, he has become an eloquent apostle of deconversion, and his disciples are many.

While critics of the faith come and go and many have minimal impact, I regard Ehrman as one of the most significant modern opponents to the Christian faith. Christians who might never be persuaded by scientific atheists like Dawkins, Harris, and Hitchens are regular readers of Ehrman’s books. He’s a secular prophet to certain evangelical and ex-evangelical readers. He has been where they are, and many are headed where he is. His books carry an unspoken but persistent sense of “Come, follow me.”

I considered Ehrman’s writings influential enough to devote an entire chapter in my book If God Is Good to his book God’s Problem. Both books center on the problem of evil and suffering, but with radically different conclusions. Remarkably, Ehrman argues there that one of his primary reasons for rejecting the Christian faith is poverty and suffering in other parts of the world. Yet he fails to realize that those actually suffering have turned to faith in Christ in huge numbers.

The subtitle of God’s Problem is “How the Bible Fails to Answer Our Most Important Question—Why We Suffer.” When reading it, I had spent the previous two years studying what the Bible has to say about suffering, why we suffer, and what God has done in Christ to address our suffering. After reading every page of Ehrman’s book I thought a more honest subtitle would be “I Don’t Like the Answers to Suffering That the Bible Gives.” (See the full chapter from my book, or an abridged version of it.)

Call to Hold Fast

I feel sorry for Bart Ehrman, but I’m even more saddened at the harm done to those who embrace his teachings. We who believe the Bible must recognize this is about our adversary, Satan, who comes to destroy and devour people through persuasive arguments, and who when he lies, “speaks his native language” (John 8:44, NIV).

In a time when “everyone has a story,” people listen to stories without discernment. The personal testimony has historically been used by faith-affirmers to reach the lost. Now it has become a tool of faith-deniers to reach the found.

There are still wonderful conversion stories, and we should tell them. But we should also, in our families and churches, teach our children to cultivate their intellects, and we should help equip them to refute falsehood and denials of the written and living Word of God. We should demonstrate the transcendent vibrancy of a generous, Christ-centered, and people-loving life, enlightened by the authentic God-man Jesus, full of grace and truth.

Finally, as we call on God to do the miraculous work of conversion in people’s lives, we “must hold firmly to the trustworthy message as it has been taught, so that [we] can encourage others by sound doctrine and refute those who oppose it. For there are many rebellious people, full of meaningless talk and deception” (Titus 1:9-10).

Photo by Jonatan Pie on Unsplash