This is a short story in which I weave together various parts of my novel Dominion. It was published in The Story Tellers’ Collection II.

The gray sky pressed down on two men, huddled close in the faint twilight.

Stoop-shouldered, leaning forward, Obadiah Abernathy stared off into empty space. He was ninety-two, son of a sharecropper, grandson of a Mississippi slave. His son Clarence, a 260-pound former college lineman, leaned over and looked into his father’s eyes. They were moist and deep-welled, eyes that had seen more than any man should have to.

Obadiah shuffled toward the front porch, Clarence holding his hand. It still felt callused and leathery from picking cotton, milling grain, shoeing horses, and scrubbing floors. But now it was feather-light, a ghost of the hand that used to whip a baseball to first, grip a chopping maul for hours on end, and overpower young Clarence in arm wrestling.

“How you feelin’, Daddy?” Clarence asked as they gingerly ascended the stairs to his brother Harley’s front door.

“Bout a half bubble off level. When you gets to be my age, if you wakes up in the mornin’ and nothin’ hurts, it’s a sure sign you’re dead.” He laughed with a delightful hiss that sounded like air escaping a balloon. “Been hard since Dani’s passin’. Man shouldn’t have to see his baby girl die. Lijah tell me that when he lost Bobby. Couldn’t have made it without my sweet Jesus. No suh.”

Two weeks after his sister’s funeral Clarence could still hear the wailing. Nobody wept like black folk. They’d had centuries of practice.

A sports columnist for the Trib, Clarence had knocked on many doors. But the door in front of him now was the hardest. Clarence let his wife Geneva do the knocking.

“Here they are, black by popular demand!” Harley’s face was framed by Malcolm-X-style glasses. A professor at Portland State, he often wore his suit and Black Muslim bow tie, but tonight had on a striking brown and yellow kente cloth.

While Harley hugged his daddy, Clarence brushed past him, to his sister Marny’s embrace. Clarence followed her into the kitchen, lured by the smell of hamhocks. Geneva stepped into the kitchen, put down her sack, and poured in bacon grease. She’d threatened to stop this to keep the men from dying of heart attacks, but they’d said if she did, she might as well kill them outright.

Aunt Ida added greens to the hamhocks. Obadiah poked his head in beside Clarence, eyes closed, nostrils flaring, breathing in the aroma with conspicuous delight. Harley stood behind both of them, trying to lean in too.

The women turned and shot mocking looks, like queens to court jesters.

“You manfolks jus’ get away, you hear me now?” Aunt Ida shooed them off as though they were stray cats. “Go discuss yo’ politics and solve the world’s problems so we can do what’s important-fix dinner!”

After forty minutes of small talk, twenty decibels louder than any white family gathering, they sat down for the meal. Mama’s dressing, loaded with onions and peppers and celery, sat at the table’s center. Huge plates surrounded it-collard greens, mustard greens, turnip greens. Big bowls of macaroni and cheese, candied yams, butter beans, and crowder peas sat alongside hamhocks and turkey, the full bird. A heaping plate of Mississippi catfish raised Clarence’s eyebrows, as did a bowl of succotash and a mess of cornbread and black-eyed peas.

There was fried chicken, fried okra, fried potatoes, deep fried pork chops, and fried green tomatoes. After Daddy said the blessing, Clarence took one slick, rubbery chitlin, for nostalgia’s sake. Chitlins objected to being eaten, but some eye-watering Cajun pepper helped him get it down.

Nothing could bring Mama back for an evening like the smells and tastes on this table. And now they were reminders of Dani, too. His precious little sister, taken so suddenly, so violently. His neck bowed low under the weight of his thoughts.

Clarence dug into the comforting fried channel catfish and Baluxi shrimp. It was enough to get the Mudcat goin’, to dredge up the deepest memories, sweet and sour, of Yazoo Basin, Black Prairie, the Bluff Hills, and the Flatwoods.

Mississippi. Dusty towns with overdressed old men sitting on porches, plucking their suspenders and pronouncing judgment on all that didn’t suit them. Corn-whisky stills. Backwater towns where the women spent their school years looking for a man to marry, then spent the rest of their lives wondering why they’d married such a fool. Clarence envisioned the magnificent antebellum mansions about which whites were so proud and blacks so angry. He lived in Oregon now, but Mississippi was his home. Yet it never had been home and never could be.

Mississippi. Dusty towns with overdressed old men sitting on porches, plucking their suspenders and pronouncing judgment on all that didn’t suit them. Corn-whisky stills. Backwater towns where the women spent their school years looking for a man to marry, then spent the rest of their lives wondering why they’d married such a fool. Clarence envisioned the magnificent antebellum mansions about which whites were so proud and blacks so angry. He lived in Oregon now, but Mississippi was his home. Yet it never had been home and never could be.

Clarence picked up cornbread and mixed it with his fingers into the collard greens. The salty, grease-soaked greens attracted stray crumbs. He licked his lips.

“This is livin’, that’s sure,” Obadiah said.

“These are serious vittles, ladies,” Clarence added.

“Just keep that pig meat on the other end of the table,” Harley said. The air filled with a sudden but familiar tension.

“You always have to get that in somewhere, don’t you brother?” Clarence ignored Geneva’s pleading eyes. “This family isn’t Muslim, and pig meat is as black as coal at midnight. So if you have all that black pride, just join in or be quiet. You know that deep-fried dish there you been eatin’ from? Bet you thought it was chicken, didn’t you? Truth is we bought it just for you, at Bits o’ Pig!”

“Just keep it goin’, brother.” Harley said the last word as if any black man off the street was more a brother to him than Clarence.

Harley’s voice sounded to Clarence like an out-of-tune guitar. It didn’t help that he was brilliant, one of the few people who could keep up with Clarence in an argument. The dinner continued in hushed tones before cautiously regaining its carefree mood.

“Let’s go to the family room,” Marny said. “Time for the menfolk to work off their dinner tellin’ stories.”

“Powerful good dinner, ladies, powerful good,” Obadiah said. “Menfolk gotsta come up with some pretty big whoppers to match this!”

Soon the stories flowed like melting butter on steaming okra. Obadiah, sitting in a rocking chair, was in the thick of them, his stories a string of pearls without the string.

“You remember ol’ Reverend Charo? Dat man had more points than a thornbush. Used to say from da pulpit in this big voice, ‘Ain’t no disgrace to be colored.’ Then he’d pause and lean forward and wink at us and whisper, ‘It’s just awfully inconvenient.’” Obadiah laughed until his eyes watered. “Sundays, now they was sumpin’. Mama, she’d put wheat starch in my collar to glue down the threads. We’d walk four miles to Sunday school, rain or shine. And did we have fun? Ol’ Lijah and me, we was always cookin’ up mischief. Mama’d say, ‘Don’t let them boys tease your sisters at church.’ Like askin’ a couple o’ Rottweilers to guard the barbecue!”

Clarence was warmed and stung by his father’s love for his brother Elijah. Obadiah wanted Harley and Clarence to be that close, but they couldn’t be in a room for an hour without tearing each other apart.

“Reverend Charo say, ‘Remember yo’ mama? How she used to hug you and tuck you in? But she gone now. Can’t tuck you in no more.’ He’d carry on, till we was all snifflin’ and sobbin’. He’d keep remindin’ us of our grandmammies and all our kin that died till we was in a frenzy. Then he’d shout, ‘But someday you goin’ to see yo’ mama again. Some day you goin’ to heaven, if you loves Jesus. There she be-arms awide open, waitin’ fo’ you. How many o’ you can’t wait for that day?’”

Obadiah’s hand shot up. “People, they be shoutin’ and clappin’, twitchin’ and tremblin.’ Now, chu’ches today, they don’t preach ‘bout heaven no mo’. Maybe nowadays we thinks this world’s our home. Maybe that’s whys we’s in so much trouble.”

Obadiah’s eyes clouded. Was he thinking about Mama? Dani? Old times with Uncle Lijah? Low and quiet, he started singing, voice wobbly.

“I don’t understand my struggles now, why I suffer and feel so bad. But one day, someday, he’ll make it plain. Someday when I his face shall see, someday from tears I shall be free, yes, someday I’ll understand.’”

It was awkward. Nobody knew quite what to do when Grandpa edged off into his other world.

“Tell us a story, Grampy,” Keisha said. “Tell us about playin’ in the Negro Leagues.” Her sweet voice reeled in her great-grandpappy.

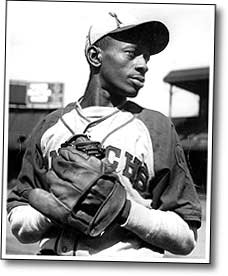

Obadiah smiled. “Shadow ball, folks called it.” He laughed like a little boy, and the children laughed with him. “We was barnstormers. Played three games a day, travelin’ by bus. Couldn’t stay in most hotels. Wrong color. But lotsa folks come to see us. They cheered us and wrote us up. Played every city. They’d hitch up the team to come see us. If they didn’t have a buggy, they’d ride two to a mule. If they couldn’t find a mule, they’d ride an armadilla.”

Obadiah’s eyes sparkled. “One year I’d be with the Kansas City Monarchs or the Indianapolis Clowns, next year the Birmingham Black Barons.”

“Tell us about Cool Papa Bell, Grampy.”

“You want fast? Only man who could hit himself with his own line drive. I watched Papa Bell run from first to third on a bunt. I saw him hit three inside-the-park homers in the same game. His roommate swore Cool Papa Bell could flip off the light switch and be in bed before the room got dark.”

Everybody laughed, revving up Obadiah’s engines.

“Tell them about Ty Cobb,” Harley said.

“Played against him in exhibition games. Cobb was an ol’ sourpuss. You could put his face on a buffalo nickel and nobody’d notice the difference.”

“What about Josh Gibson?” Ty asked.

“You want a slugger? Josh hit more five-hundred-foot home runs than Ruth. Only man to hit a ball clean out of Yankee Stadium. One season Josh hit seventy-five home runs.”

“If Gibson was playin’ in the majors today,” Harley said, “what do you think he’d hit?”

“Oh...,” Obadiah paused. “Maybe .280, with thirty home runs.”

“That all?”

“Well, you has to understand...he’d be eighty-five years old!”

When the laughter stopped, Ty asked, “Was Josh Gibson the best?”

“No. No. Satchel.” He grinned. “Satchel Paige.” He nodded vigorously. “I’s not just black as coal, chillens, I’s old as coal! Played with Satch on two teams, and played against him more than I cares to remember. No man never pitched like Satchel. He’d go into a game sayin’ he’d strike out the first nine men. Usually he did. First baseman didn’t touch the ball for three innings. Once we put a batboy out on first ‘cause we knew he’d never have to do anything. Another time all us infielders sat down around second base and played poker till somebody finally got wood on the ball. It was the fourth inning. When I was with the Clowns, the catcher would sit in a rockin’ chair. Ol’ Satchel, he could pitch a greasy pork chop past a hungry coyote!”

“No. No. Satchel.” He grinned. “Satchel Paige.” He nodded vigorously. “I’s not just black as coal, chillens, I’s old as coal! Played with Satch on two teams, and played against him more than I cares to remember. No man never pitched like Satchel. He’d go into a game sayin’ he’d strike out the first nine men. Usually he did. First baseman didn’t touch the ball for three innings. Once we put a batboy out on first ‘cause we knew he’d never have to do anything. Another time all us infielders sat down around second base and played poker till somebody finally got wood on the ball. It was the fourth inning. When I was with the Clowns, the catcher would sit in a rockin’ chair. Ol’ Satchel, he could pitch a greasy pork chop past a hungry coyote!”

Geneva passed out the sweet potato pie. Obadiah smiled broadly. He held it up under his nose. “Um, um, um.” He placed it on his lap so his hands were free to talk.

“My son, the sportswriter,” he looked at Clarence, “always told me he’d take me and his brother to Cooperstown one day, and we’d look at those pictures, and I’d show ‘em Satch and Josh and Cool Papa. Even find ol’ Obadiah Abernathy in some of them Shadow Ball pictures, I reckon.”

Clarence squirmed. He’d promised his daddy they’d go to the Baseball Hall of Fame. He’d thought about it every year. But Cooperstown, New York, was on the other side of the country. There were always reasons not to go. And Harley was the biggest.

“We was sharecroppers in a bitty Mississippi town,” Obadiah said, “so far down they had to pump in the sunshine. Lived in an ol’ shotgun house. We chillens slept with each other, cuddlin’ to stay warm.”

“Yuck,” Jonah said.

“No yuck about it, boy. Sometimes my nose so frozen, don’t know what I’d done if brother Elijah hadn’t been there to snuggle. They was hard days, but good ones.” His eyes watered again. He looked up at the ceiling as if trying to peer beyond it. “I miss eatin’ sowbelly and corn pone and slicin’ up the catfish fresh out o’ the river and sittin’ on the porch those warm nights-Lijah and me and Daddy and Mama and the rest. We’d jus’ watch the lightnin’ bugs, lookin’ magical, like somebody sprinkled livin’ pixie dust in that ol’ creek. We’d listen to those hound dogs bark and look up at those stars and see the face of God. True brothers, me and Elijah.

"We went through that Depression together. Couldn’t find no work in Mississippi, so we rode the rails. We’d get off town to town, search for work all day. Most nights we was outside or on the rails. We’d find newspaper, lay it over us, curl up and put our arms around each other jus’ to keep from freezin’-grabbin’ on to life, like when we was little. We’d pray, quote the Good Book, talk and laugh the night away, just Jesus and me and Lijah, brothers through and through.”

“I wish Uncle Elijah could come for Christmas,” Clarence said.

“You and me both,” Obadiah said. “Miss Lijah, surely I does.”

“Where we meeting for Kwanzaa?” Harley asked.

“Don’t know about Kwanzaa,” Clarence said, “but Christmas is at our place, right Geneva?”

Harley shook his head. “You celebrate an independence day that didn’t consider blacks worthy of independence. You celebrate a Thanksgiving of hoodlums who stole America from its natives. And you celebrate a Christmas about a white man’s religion that oppressed your ancestors.”

Clarence’s eyes burned, but he held his tongue.

“I’m an African. That’s why I celebrate Kwanzaa, not Christmas.”

“Well, I got news for you,” Clarence said. “Kwanzaa isn’t from Africa. It was invented in Los Angeles, by Americans!”

“It was invented to commemorate what Africa is about. Which you’ve obviously forgotten.”

“Our ancestors came from Africa. But we’re Americans. If our kids are going to make it here, we’ve got to quit telling them they don’t belong.”

Harley put his hands up. “Now that the wood’s all split, the water’s drawn, the cotton’s picked, and the rails reach coast to coast, now that the ditches are dug and there’s just shoes left to be shined, now they tell us they’ll give us a chance. Well, they’ve been liars all along and they’re still lyin’! So excuse me if I don’t join you in shufflin’ for ‘em, Tom!”

Clarence stood, shoulders tense, well aware his two-hundred-sixty pounds cast a formidable shadow. “To you anyone who makes a living outside of a government agency or a black studies department is an Uncle Tom.” He ducked into the kitchen and slammed his fist on the counter. Right about now, he knew, Dani would have come in, cooled him down, reminded him he and Harley were brothers.

Clarence breathed deeply and returned to the family room as his father said to Harley, “Nossah, son, that’s poppycock, pure and simple. Not all white people’s like that. Yeah, there’s racists--white and black. You raised in the garbage, you can’t help but stink. Some gots it so bad they’ll never change, and you just got to let ‘em go. Like Pappy said, ‘Don’t never try to teach a pig to sing.’”

“What?” Geneva asked, laughing.

“It wastes your time, and it annoys the pig.”

“Daddy, I wish you’d come to the true faith of the black man,” Harley said.

Obadiah sucked in air and sat up straight. Every back in the room tensed. “Hear me, son, and hear me good.” The voice was clear and firm. “I knows the true faith of the black man, the brown man, the red man, the yellow man, the white man. Every man. It’s a faith in Jesus. He say, ‘I am the way, the truth and the life; no man comes to the Father but by me.’ The only train that’s goin’ to take you to the Promised Land is the glory train, and Jesus is the conductor. When he hears that whistle, ol’ Obadiah Abernathy’s gettin’ on board. I’m gonna make it to that Promised Land.” His thin voice started singing, “‘Git on board, little children, git on board. De gospel train’s a comin’, git on board.’”

Clarence looked down uneasily, but suddenly Daddy’s eyes cleared and he pressed his hands on the arms of the rocking chair, gazing at Harley.

“I won’t let you attack the faith that’s been the foundation for this family, for your mama and my mama and daddy, and their mamas and daddies before them. You hear your papa talkin’, Harley?”

“My name’s Ishmael Salid.”

“Don’t tell me what yo’ name is, boy!” Obadiah stood up with startling force, shaking his finger. Daddy looked like he was about to bring out a hickory switch, and Clarence relished it. “I’m the one that gave you yo’ name. Me and yo’ sweet mama. I love you, son, but you’ll always be Harley Abernathy. Somebody else can call you Elijah Mohammed or Kareem Abdul Jabbar or Sister Souljah, but I gave you yo’ name and I’s gonna call you Harley till the day I die and then some. Nuttin’ you says gonna change that. You hear me, boy?”

“Yes, Daddy,” Harley said. “But when you’ve been emasculated by white Christians for four hundred years, you want to do something that affirms your black manhood. Islam is Afrocentric; Christianity is Eurocentric.”

“Baloney,” Clarence said. “Both of them started in the Middle East, and there were black Christians in Africa six centuries before Mohammed.”

Harley ignored Clarence. “Let me ask you one thing, Daddy. Those Mississippi cops nearly beat you to death for bein’ black, didn’t they? And that place was full to the brim with Bible believin’ church people, wasn’t it? Does that tell you something? One of those crackers was a deacon in the Baptist church, remember? Now I want you to tell us all, Daddy, did you ever hear any white Christian church leader stand up and say to the community, to the black churches, to the newspaper, to anyone, ‘This is wrong. We’re sorry. We will no longer tolerate the lynchings, the beatings, the humiliation, the cruelty! We’ll kick the Klansmen out of our churches and help the oppressed and stand up for justice.’ Did you ever hear that from a white church leader? I want the whole family to hear your answer.”

Seventeen family members sat in breathless silence in the crowded living room, all of them looking at Obadiah. He sat silently for a long time, eyes down. Tears fell into his lap. Finally he looked up.

“No. I never did hear that. I wish to Jesus I would have.” He fought to gain control of his voice. “But that’s not God’s fault, son. And my faith’s in God, not men. Not white men, not black men. My faith’s in a God who ain’t black or white, but who made both and died for both.”

Obadiah looked at Harley, then Clarence. “It grieves this ol’ man to see my sons fight. I don’t want my Ruby or my Dani lookin’ down here and havin’ to see it neither. You’re brothers-don’t that mean nothin’ to you? I’m old as dirt, but I ain’t mulch on the flowers yet. I gots me a third-grade education, but I seem to know some things you college graduates don’t. I’s still your daddy. Now I gots a few things to say, so shut up yo’ mouths and listen, both of you.”

Everyone sat wide-eyed and attentive. “Clarence, you should show more respect for your brother. Yeah, I disagrees with him too, but sarcasm and venom ain’t the way to convince him. I wish I heard more love in your voice, more kindness to your brother. Yo’ mama would want that. You knows the words of the gospel, boy. But I’s sorry to say, you’s missin’ the music.”

Clarence looked at the floor.

“Bein’ angry ‘n bitter won’t bring your sister back neither. Truth be told, she wouldn’t want to come back. Now you, Harley,” Obadiah said. “You read Revelation, last three chaptas. Almighty ain’t gonna adjust his plans to fit your beliefs or Minister Farrakhan’s or nobody else’s. You better start changin’ your beliefs, ‘cause the Almighty ain’t gonna change his.”

Little Keisha stared up at her grandfather. Catching her eye, his voice became gentler. “Now, the rest of you, hear this old man and hear me good. Not all my dogs is barkin’ anymore, but I can tell you what I knows, and I knows this-there’s bad Christians and there’s good Christians; there’s phony Christians and there’s real Christians. The devil can go to church once a week. Nothin’ to it. It’s livin’ it that counts, and the people that live it, those are the real Christians. The way I reads my Bible, anybody who hates a man for the color God made him isn’t filled with God, he’s filled with the devil. There’s real money and there’s counterfeit-don’t let the counterfeit stop you from believin’ there’s the real thing. People’s always gonna let you down.”

He’d been talking fast, but his speech slowed to a crawl. “But my Jesus, he won’t never lets you down. Never. Yessir, my Lord tooks my daddy and mama, my Ruby and nephew Bobby and now my Dani, he tooks them all away from me, and Moses and all my brothers and sisters ‘cept ol’ Lijah, but he never once tooks away himself from Obadiah Abernathy, and that’s the gospel truth.”

A hush permeated the living room. Clarence and Harley, both ill at ease with the tears flowing down their father’s cheeks, lowered their heads.

Geneva got up and collected dessert plates. The other women followed.

“Close to God, my Ruby was,” Obadiah said to no one in particular. “And now she’s in his backyard. When the chillens in bed, we sat on our porch counting cricket chirps and watchin’ stars. Used to ring that ol’ porch bell, Ruby did. Meant it was suppertime, time to come home. Sometimes this ol’ boy hears that bell a ringin’. Time to come home.”

Obadiah tilted his head, then hummed. While Clarence and Harley squirmed, Daddy listened to the music no one else could hear. Obadiah looked boyish, as if running unrestrained through the meadows of childhood. Was he remembering childhood, Clarence wondered, or anticipating it?

“Oh Freedom, Oh Freedom, Oh Freedom over me,” Obadiah suddenly sang. “`And before I’ll be a slave I’ll be buried in my grave, and go home to my Lord and be free. Git on board, little chillen’, git on board. De gospel train, she’s comin’, git on board.’” His voice changed. “Amazin’ grace, how sweet the sound that saved a wretch like me; I once was lost, but now am found, was blind, but now I see.’”

Most of the family sang along. Harley picked up a newspaper from the coffee table and buried his nose in it.

“When we been dere ten thousand years, bright shinin’ as da sun, we’ve no less days to sing God’s praise, dan when we first begun.” The tears poured down the old man’s cheeks as he stared out the window.

Clarence followed his daddy’s gaze.

He couldn’t see anything outside but darkness.

* * * * * * * * * *

Clarence rushed into the hospital room. His father looked so small lying on that bed, tethered to an oxygen tube.

“How are you, Daddy?”

“If I was a hoss, they’da shot me already.” Obadiah chuckled feebly. “But I’s still a man.”

“You’re the best man I’ve ever known.”

“You should get around mo’, son. Meet mo’ people.”

“I mean it, Daddy. You were always a hard one to disobey, but you’ve been everything I could ask for in a father. If I could be to my children and grandchildren what you’ve been to me...”

“Give ‘em yo’ time, son. No substitute for yo’ time. Learn those younguns God’s ways. Teach ‘em who they is-chillens of the King. Some man treats ‘em like a dog, he gonna have to face their Daddy, the King. Chillens grows up real quick. Don’t miss the chances you got now. Won’t get ‘em again, boy. Won’t get ‘em again.”

“I called Uncle Elijah this morning. Wanted me to tell you he’s prayin’ for you.”

“Best brother a man could have, Lijah. Kept each other warm those cold nights. Had us some fine times, we did. Wish I could be home with ‘im. Miss ‘im terrible. A true brother. Wish you and Harley could...”

“I know.” Clarence choked. “I’m sorry we never got to Cooperstown.”

“It ain’t too late.”

Clarence looked at him, not sure what to say.

“I wants you to take Harley. You can do it. They gots ol’ pictures. Look for me. Twenty-two years in Shadow Ball. Your ol’ daddy’s gots to be in some of them pictures!”

“But it’s you I wanted to go with, Daddy.”

“Don’t worry none about me, son. I’s goin’ to the real Hall o’ Fame.” He laughed and looked at Clarence with soulful eyes, the light inside flickering in eternity’s winds.

Harley walked in the door. He nodded at Clarence and stood on the opposite side of his father’s bed.

“My boys.” Obadiah smiled. “Brothers,” he whispered. He lay still, closing his eyes. The brothers stood there, not looking at each other, both wondering if those eyes would open again. Three minutes later, they did.

“I hears that whistle blowin’,” Obadiah said. “Train’s a comin’. Folks a gatherin’.” Eyes closed, he said, “Who’s dat walkin’ beside me now? Tall as an oak. Where’d ya come from, big fella? These ol’ legs don’t feel so sore. Now who’s dat up ahead? Whose face I see? O, my sweet Jesus. It’s you. It’s you!”

Obadiah grew quiet. Clarence checked his pulse. Suddenly Daddy’s eyes popped open, not blinking, but watering up, focused on something beyond the room.

“Who dat, now? Daddy? O Daddy, what you told me was true. And... Mama? Yes, me too, Mama. Me too. Terrible much.” Silence again. “Moses! How are you, brother? How long’s it been? But where’s my Dani? There she is! O Dani, I hasn’t stopped cryin’ for you, little girl. And who’s this one? Bobby, that you? Leukemia’s gone now, ain’t it? O sweet Jesus, sweet Jesus. I never knowed such joy. Thank you, my sweet Jesus.”

Clarence and Harley stared, wide-eyed, as the tears streamed down their father’s face. “He’s hallucinating,” Harley whispered. Clarence nodded, then moved over to Harley’s side because his father’s head was turned that way. The brothers stood shoulder to shoulder, leaning over their father, wanting to hear the fading voice.

“My, oh my, can’t believe my eyes. Who’s dat woman? Uncommon pretty, she is. Missed you terrible, Ruby. Got lonely jus’ me and the fireflies, countin’ cricket chirps and watchin’ the stars all by ourselves.”

Clarence looked at Harley. Was it possible...?

“Wait a minute there.” Obadiah said, “Who dat behind you? Lijah? That you, brother?”

As Daddy shed more tears, Clarence and Harley let out their breaths at the same moment. The old man’s body jolted.

“You all come out to get me, didn’t you? I hears that ol’ porch bell a ringin’. Time to come inside, ain’t it? Gospel train’s a comin’. Obadiah Abernathy’s on board. Time to cross dat ol’ Jordan. Time to...”

Obadiah’s eyes grew big, but his pupils contracted as if seeing a bright light. Then his eyelids fell over them, like blinds suddenly tugged shut. He gasped air like it was his last breath.

Or his first.

Clarence and Harley looked at each other in disbelief. Only an instant before the empty shell in front of them had still contained a man.

“Oh...Daddy,” Harley sobbed, taking off his glasses.

Clarence fell to his knees, laying his head on the bedspread. “We gonna miss you, old man...” He choked out the words. “We gonna miss you terrible.”

After ten minutes, Harley and Clarence helped each other out into the hall.

“Antsy?” Harley said. Clarence hadn’t heard his brother call him that for twenty years. “Must have been the painkiller or something. But for just a moment, I thought maybe Daddy was really...I don’t know. Did you ...?”

“Yeah, I did. Up until he thought he saw Uncle Elijah. But I just talked to him a few hours ago. Lijah’s still in Mississippi.”

“One thing’s for sure,” Harley said, “Mississippi and heaven aren’t the same place.”

Clarence nodded and cleared his throat. “Harley?”

“Yeah?”

“Would you mind comin’ to my house for a bit? I’d like to talk...if that’s okay with you.”

“Well, I got papers to grade and I need to tell my family about Daddy. But...yeah, I guess I could come by. Let me call home first.”

When they got to Clarence’s they sat in the living room, eight feet apart. Geneva brought coffee to Clarence and tea to Harley. The phone rang. Geneva answered. Both men listened.

Geneva put down the phone, face pale. “It was your cousin Jabo in Jackson. I left him the message about Daddy half an hour ago. He called about Uncle Elijah.”

“I’m sure Lijah’s taking it hard,” Clarence said. “They were so close.” Harley nodded.

“It’s not that,” Geneva said.

“What?” Harley asked.

“Uncle Elijah passed away.”

The two brothers stared at each other across the room.

“When?” Clarence’s voice was hoarse.

“Four o’clock this afternoon, Mississippi time.”

“That means he died...” Clarence stopped.

“An hour before Daddy.” Harley put his hands on his face. Clarence did the same.

Clarence made the long walk across the living room and knelt next to his brother. He put his arms around him. They embraced for the first time in twenty years, the first time since Mama died. They hugged each other like two freezing men in a railroad car, hanging on to life.

Clarence could only think about going two places: One, to where his daddy and mama and Dani and Uncle Lijah were.

The other, to Cooperstown’s Hall of Fame.

For more information about this book, see Dominion.

Photo by Fred Kearney on Unsplash