I was recently asked the following question on Facebook:

"I had a woman come to my door today, wanting to share the gospel. Why is it that even though I know what I believe and why I believe it, that it is so hard to share with others? She was a Jehovah's Witness, and asked if she could come back to share a scripture again. I told her yes. I will be better prepared next time, but how do I become better prepared?"

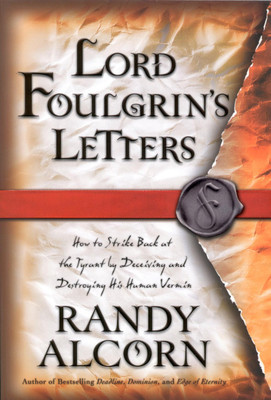

In Letter 30 of Lord Foulgrin's Letters, I have one demon instructing another one how to keep a Christian from sharing the gospel...

Postponing Evangelism

My delinquent Squaltaint,

You’re concerned the sludgebag Ryan is encouraging Fletcher to “share his faith.” You blame Dredge for failing to restrain Ryan and assure me you’re sincerely laboring to derail his efforts. In Charis sincerity may matter. All that matters in Erebus is results. Stop whining. Come out of your corner not swinging blindly, but with a thought-through strategy to knock out Fletcher.

Since it’s what the Enemy uses to change vermin destinations from hell to heaven, obviously you must keep Fletcher from evangelism. But don’t bother trying to convince him it’s badto evangelize. Let him think it’s good, admirable. Just as long as he doesn’t actually do it.

The best strategy is to keep him from grasping the stakes, so he has no sense of urgency. Even Bible-believing churches help us here. According to the records you sent, in the past ten years Fletcher’s pastor has preached only one message on heaven and none on hell. That track record will presumably continue, and Fletcher will get the impression eternity is unimportant. He’ll think of hell as unreal and heaven as intangible and undesirable. Both will seem like fantasy realms with no bearing on his present earthly life.

Next, persuade your maggot-feeder he must be low-key, careful not to bowl unbelievers over with his new faith, lest they see him as a fanatic and get “turned off.” By all means don’t let it occur to him to quietly tell them what the Enemy has done for him. Let him imagine that this should be done gradually, only when they ask, or only after a long (as in endless) period of being a “good example.”

No man is won to the Enemy simply by the moral behavior of another. No one has ever gone to heaven just because he saw a good example. No one has ever escaped hell because some other man was a Christian.

Let Fletcher be a “good example” until he’s blue in the face—as long as he doesn’t explain the forbidden message. Look around you, Squaltaint, and you’ll see innumerable Christian sludgebags who’ve been good neighbors and model coworkers for decades. But they’ve never actually told those around them what it means to be a Christian. Many of them imagine by now the message has somehow magically gotten across, but of course it hasn’t. Excellent.

Fletcher made the statement to Ryan he’d like to share the gospel with his wife and mother-in-law “when the time is right”? This frightened you, but it can work to our advantage. Don’t let him grasp the Enemy’s notion that evangelism is one beggar telling another where to find bread. Instead, turn evangelism into something more complex or obscure, something that will happen one day, but never today.

Fill him with an irrational dread of bringing up the Carpenter and the forbidden message in conversation. If the vermin analyzed it, they’d be on to us. What else but our efforts could explain why they get so apprehensive about doing for someone what they believe is the biggest favor in the universe—telling them about the Enemy’s plan to save them from hell and give them heaven?

Don’t let Fletcher ask himself why a man from Portland should care about what a man from Chicago thinks of him as they both fly to Philadelphia. Why, when he will never see this man again (unless he accepts the message, in which case he’ll be deeply grateful), should he be so frightened of the man’s rejection? Why would they feel so hesitant about telling people what’s clearly in their best interests? Don’t let the obvious absurdity settle in, or he may catch on it’s we who are playing tricks on his tiny mind, fueling this irrational fear.

Never let him see the incongruity of how he could talk with someone on that airplane and share a myriad of opinions about business and politics, and make a case for why a team will win the Super Bowl, but dare not make a case for the Carpenter. Don’t let it dawn on him they’re all going to die soon. Perhaps in an hour, a day, a week, a year, at most a few decades. Never let death seem imminent.

The one thing they consider most important to talk about eventually is the one thing they can’t talk about now. Our perfect timing, our “just the right moment” boils down to this: never, until it’s too late.

Keep him ignorant of church history and forbidden squadrons across the globe. The Enemy may try to point out to him that while his brethren risk imprisonment and death, Fletcher is unwilling to hazard a raised eyebrow or a disapproving glance.

Jordan’s been thinking about sharing the forbidden message with his own father too? I see the geezer’s health is bad, that Scuzfroth predicts a heart attack within a month. Good—he’ll be in hell before you know it. Fathers are hardest of all. Your report says your vermin’s father intimidated him, called the shots, and now thinks his son’s new faith is a passing phase, part of a “midlife crisis.”

Quick death is the best we can hope for with unbelievers. If he doesn’t die immediately, prompt Fletcher to watch him waste away. Let him visit him, tenderly care for him, and lovingly “respect his wishes” not to hear the forbidden message.

Consider the extent of our accomplishment—they would rather see a loved one go to hell than be seen as pushy by insisting on telling him the truth. The Enemy calls them to be truth tellers in the name of love. We call them to be truth withholders in the name of “not being pushy.” Don’t let it dawn on him that one moment after he and his father die they’ll both regret the same thing—that he didn’t tell his father the truth one last time (in some cases, one first time).

It’s delicious what we’ve pulled off here—Christian family, hospice workers, nurses and doctors caring for the dying, and in the interests of ethics or professionalism withholding what their patients long for. Christian counselors meet with troubled, desperate people whose lives have fallen apart. But because they came to get help with their addictions or their marriages, the counselors consider it unethical to exploit them by sharing the forbidden message. We have countless Christian teachers dealing with lonely, troubled, and desperate students. They could speak to them about the Carpenter, but don’t because they fear reprisals or have no sense of urgency.

Think of it—our prey cite endless ethical and legal reasons for not obeying the Enemy’s command!

Delay. Procrastinate. Postpone. This is our evangelism strategy. If we do our job, people will die of thirst a few feet away from water bearers who don’t want to impose their water on others.

“I’ll share the truth when the time is right,” your vermin Fletcher said. Your job is simple—make sure the time is never right.

Populating hell one image-bearer at a time,

Lord Foulgrin

One rule I go by—the biggest obstacle is just opening your mouth and starting talking about the Lord and the gospel. Once you start, you're committed. It's speaking the first words. I tell myself, stop waiting and praying for the opportunity, this IS the opportunity, and once I start, the pump is primed and God guides. Of course, studying Scripture to know the gospel you're sharing is vital too.

Read more of Lord Foulgrin's Letters.

Photo by Priscilla Du Preez on Unsplash